Cleaning out my mother’s house after she died revealed the usual postmortem waste. Old checkbooks and old budget books, framed and unframed college and high school diplomas, faded proof photographs from her high school graduation, closing documents pertaining to a house sold back in 1964. I found a box she’d taken home after she’d cleaned out her mother’s house—investment documents that went back to the 1980s and a heap of costume jewelry—and boxes that my father kept from his mother. Her strings of pearls, with tags on each that name the country that they came from. Photographs and strips of film in cardboard rolls: my father with a former girlfriend. Sag Harbor in the 1950s. Miami in the 1920s—saw palmettos, hunting rifles—in a black-paged album with a shoelace wrapped around the spine. Another album packed with photographs of rock formations—my father, the geologist, did better with rocks than people—and a cedar chest packed high with doilies that my great-grandmother knitted. The quilt she made out of suit fabric scraps in Golden Gate Park, after the 1906 earthquake. Another cedar chest, wool blankets, brought down from New York in 1970 and never used thereafter. A steamer trunk filled with the Miami stuff my mom collected: postcards and old swizzle sticks and PanAm napkins, newspapers and magazines from the days after Hurricane Andrew. Every Easter hat and bonnet that I ever wore. My baby clothes. Report cards. And roach droppings and egg casings and termite frass and actual, live termites, working at a window frame in an industrious, grub-colored line.

What surprised me, among all of this, concealed within a hollow chamber at the bottom of a set of bookshelves my mother built with her own hands, shelves that reached from floor to ceiling, covering the wall of my old bedroom, painted forty years ago in petal pink, was a document about a murder that she’d witnessed. I knew she’d put a manuscript under those shelves, a memoir in eight binders that she’d handwritten and typed in 1990, but I never knew about this murder. The pages are typewritten—I found two other copies hidden elsewhere in the house. Each one has the same preamble at the top:

The following is my description of a murder that I witnessed. The time was probably July of 1962. The location was Cape Florida state park, on Key Biscayne. I was nineteen at that time. Jean is my older half-sister. My narrative begins in the parking lot of a restaurant in south Dade. I was sitting in the front seat of Jean’s car. She was sitting in the driver’s seat. A man was seated in the car next to us. He was talking to Jean. She called him ‘Tony’ but I did not hear her call him by that name until later.

In the narrative that follows, my mother’s sister throws her in a car trunk and drives her out to Key Biscayne, where they meet four men: Tony and two henchmen with a man, the murder victim, pressed between them. My mother recognizes him as Mr. Tyler, the owner of a restaurant where she used to work.

Upon recognizing me Mr. Tyler suddenly became very “proper.” The two men loosened their grip on him. Mr. Tyler straightened his tie and tried to look more presentable. He was wearing a business suit. He said something about “being with a lady.” He was referring to me! I had never felt so unladylike before. My skirt was wrinkled and my blouse was hanging out in various places. I shed a few tears. I thought Mr. Tyler was being sarcastic. But I soon realized that Mr. Tyler’s attitude toward me was pure kindness, not sarcasm. I said that my feet hurt and I wanted my shoes.

“The lady needs her shoes!” Mr. Tyler shouted at Jean.

“Where are we?” I asked him.

Mr. Tyler had a beautiful smile. “In Paradise,” he answered. I thought that was a very strange answer.

“What’s Jean doing here?” I asked. All the men laughed. Jean threw my shoes at me. One of them hit me in my head, making my headache worse. I began to cry again.

My mother’s sister orders them to get going. My mother describes the physical appearance of Tony and Mr. Tyler in detail, then describes the unpaved parking lot and sandy woods beyond it. They’re near a beach. They find a trail.

One of the young men, leading the way, was carrying something over his shoulder. It looked like a satchel for a tennis racket. But the object inside was bigger than a tennis racket. As I studied the shape I realized that the satchel contained a shovel. There were six of us walking through the woods, three couples. There was about twenty feet of space between each couple. We carried on private conversations as we walked. It was evening, near sunset, and the light was getting dim. My fear was building. I asked Mr. Tyler again what all this was about. He repeated the strange comment about “a walk in the woods.” I began to understand that this was a code for something else.

They walk until they reach a shallow grave. Mr. Tyler, without putting up a fight, sits down in it. Jean gives my mother a handgun so small that it looks like a toy—she calls it a “Hariot”—then points a much larger gun at her. She wants her to shoot Mr. Tyler. In a sequence of events that is at once heroic and insane and brutal, my mother throws the handgun in the scrub, manages to grab her sister’s gun and empty all six rounds (hitting Mr. Tyler in the left elbow accidentally), then Tony, who also has a gun, shoots Mr. Tyler in the jaw. Tyler isn’t dead—there’s a horrendous, high-pitched scream—until Tony shoots him again. Then he sits atop the victim’s chest, presumably to hammer out his teeth. My mother seizes Mr. Tyler’s dentures, and, unseen by Jean and Tony, who are arguing about whose fault this is, hides the dentures under the dead body’s legs. She runs.

I had no sensation of my feet touching the ground. I didn’t know where I was going. The sun had set and there was very little light left. Suddenly I fell. I dropped off a small ledge and rolled. I reversed the direction of my roll, going back the way I had come from. I knew I’d fallen off something. Perhaps it would be big enough to hide me. I rolled toward the small ledge that I had fallen from. I expected to stop when I got to it. But to my surprise, I didn’t stop. I kept going right under it. The ledge was two to three feet above ground level. There were weeds growing on top of it. Some of them hung down. I was almost completely concealed.

She stays hidden in the hole under the ledge for the rest of the night. The hollow turns out to be shared with a feral pig, who heaps dirt at her, offended at her taking up its space. She talks to the ghost of an ex-boyfriend as she hides, nearly revealing her location, and finds a policeman in the morning. Somehow, the body is not found.

In a folder in my mother’s desk, as I made my slow way through the process of emptying her house, I came across a yellowed clipping from the Miami Herald. “Human skeleton uncovered in park,” the headline reads. The article goes on to say that the remains were found in Crandon Park, in Key Biscayne, in shallow soil, and appear to have been there for several years. There are dentures at the scene. In a photograph across the top, a homicide detective holds—with ungloved hands—a jawless skull. The date of the story is July 16, 1991. Later, on the internet, I found a follow-up from three months later. It states that the remains “may have been there for 25 years,” that the victim was a male in his 50s who stood about five feet, six inches tall. It also says that there’s no evidence of trauma.

The date on all three copies of my mother’s narrative about the murder is October 25 of the same year. She’d read the article before she wrote the story. After a brief search of the internet, I found an obituary for A. M. Tyler, owner of the chain of Tyler’s restaurants. Banker, grandfather, great-grandfather, member of the Central Baptist Church, avid fisherman and hunter. He died at his summer home in Georgia, in 1978.

My mother told me another version of the Tyler story when I was around ten. She left out the part about the murder, and talked instead of being very scared of something, running through the woods, dashing into a hiding place that had a pig inside it. In one version, an archangel appears above her. He witnesses her dive into one end of a hollow log and laughs at her apparent transformation—the pig runs from the other end of the log a moment later. She described the archangel as very tall, like twenty feet, and joyful. He laughed merrily over the pig for quite a while.

In my freshman year in high school, my mother told me that there was a man above the log, and that she’d been so frightened of his presence she’d thought maybe she had died, and asked him, “Jesus, is that you?” The man responded just like Jesus would, she figured: “Some people know me by that name.” In fact, my mother wanted me to understand, the reason for this man’s strange answer was that he was James Jesus Angleton, then director of the CIA. Who was on a mission for the KGB. That year I wrote a paper on the “theory” that Angleton was actually a mole, earning my first F in high school. (“Well,” my mom said of my teacher, “he’s a real right-winger, isn’t he?” He slipped some young-earth creationism into his teaching of world history, so, probably, yeah.)

This was the relationship that I had with my mother: I was somebody who listened to her. Everything she told me was meticulously detailed, vivid—I loved hearing her stories. Her childhood, her parents, old Florida, some crazy Russians. From the age of nine, when she started telling me things that she remembered, everything was remarkably consistent—the Angleton/archangel difference is the only disparity that I remember. There was a lot of CIA and KGB stuff, a Russian-infiltrated FBI, her connection to a family that ran a gambling operation in the 1950s. That poor dead boyfriend. (Murdered.) The father of the poor dead boyfriend. Another murder that she’d witnessed as a child. She told me about recovered memories, reincarnation, being arrested at a civil rights protest in 1963, being abducted by the KGB and flown to Moscow. The horrors that she witnessed there. I knew she was writing this stuff down—I remember being mad at her when I was ten, feeling I had lost her to her “book”—and always hoped one day she’d let me read it. I wanted to know all of it, and understand it. I always believed that it was true.

Now here I am, with these eight binders. The only description I can give to all of it is incredible—in, as my friend the novelist Suzanne Rindell puts it, “the fullest meaning of the word.” I thought that reading my mother’s manuscripts would make things clearer. Even, in my twenties, as I began to pull away from her and doubt her, I’d hoped someday she’d let me read this stuff and finally explain it. Which parts really happened. Which parts she was making up. Now all I want to do is talk to her, and ask these things. Sometimes, reading it, I think I understand what happened—she had shock treatments at 17, she writes, and lost her memory for chunks of time thereafter—and I feel like I can draw a line between autobiography and fiction. And all I want to do is talk to her, and comfort her, and tell her at least I can bear witness to the traumas that she lived through, and try to sort out with her which parts really happened, and maybe prove that all it was real. Then I go back through the Moscow stuff, which has to be impossible—no U.S. citizen has ever been exfiltrated by the KGB, my husband points out—and see her detailed drawings of the buildings she was in, the road she saw, and think, it can’t be true. Same as it can’t be Mr. Tyler in that grave.

I don’t know what to make of what she’s written. I miss her. For now I’m keeping all her manuscripts, like ashes, near me in neat white boxes in my room.

Read, read, read

I haven’t been reading much else lately apart from my mother’s manuscripts. Luckily, my friend Anna recently suggested two novels by Gwendoline Riley, First Love and My Phantoms, which I’m reading now and thoroughly enjoying. In his review of both in the New Yorker, James Wood calls them “savage” and “vengeful,” books that “relate to each other like twitching limbs from the same violated torso.” They’re both about bookish young women with bad parents, and spend much of their time skewering the mothers, who are unloving, frivolous, and fearful of the world.

What makes me recommend them, apart from the writing itself, which is sharp and spare and often as pretty as it is unkind, is the way they make me feel about my mother. To quote Wood again: “One thing that heartlessly unsentimental writing does is force the reader to generate the very sympathy such books lack.” I sympathize with Riley’s pair of helpless mothers, who might be superficially the opposite of mine, and find in them a source of more compassion. Which is part of the absolutely magic alchemy of writing: a story can introduce you to unlovable people, and make you love them.

On the other hand, some characters are so unlikeable you hate them through the final page. In Andrew Ewell’s debut novel, Set For Life, a failed writer and teacher of creative writing confesses to an alcohol-soaked, career-ending affair. Much of the joy of hating Ewell’s narrator comes from the distance between narrator and author: his character is unaware of just how badly he’s behaving, even as he overhears a passage that his wife (a successful novelist) has written about him:

“ ‘He wasn’t always that way,’ ” she continued. “ ‘He used to be ambitious, hardworking, industrious, even. But he became too resentful of other people’s success. He prided himself on being a realist—he thought he always knew the right answer—but actually he was a fantasist. He was delusional and sentimental and nostalgic.’ ”

Boy, I thought, this was one sad sack she was writing about…. Whose life and times had she pillaged now? One of her sister’s boyfriends?

“There’s Always Been Trouble in the ‘Groves of Academe,’” as A.O. Scott writes in the New York Times (gift link). Scott is reviewing a book published in 1952 by Mary McCarthy, comparing the political upheaval of her fictional college campus—and that of campus novels throughout the twentieth century—with the current crises over the war in Gaza and DEI. True to this tradition, Ewell’s narrator fumbles his way into the crosshairs of a group of students who find his discussion of Jane Austen “offensive,” “rooted in the patriarchy,” and “gendered.” When he looks to the lone male student in his classroom for support, he finds him drawing on his forearm with a pen.

Matt news

Matt is about to start a new job with the New York Times. (!!!) He’ll be covering the U.S. federal judiciary as a legal correspondent. Here’s the official press release, with links to his most recent and best work. If you have any insights about the federal judiciary to share, or any hot tips for the Times, you can reach him at schwartz79@protonmail.com.

A picture

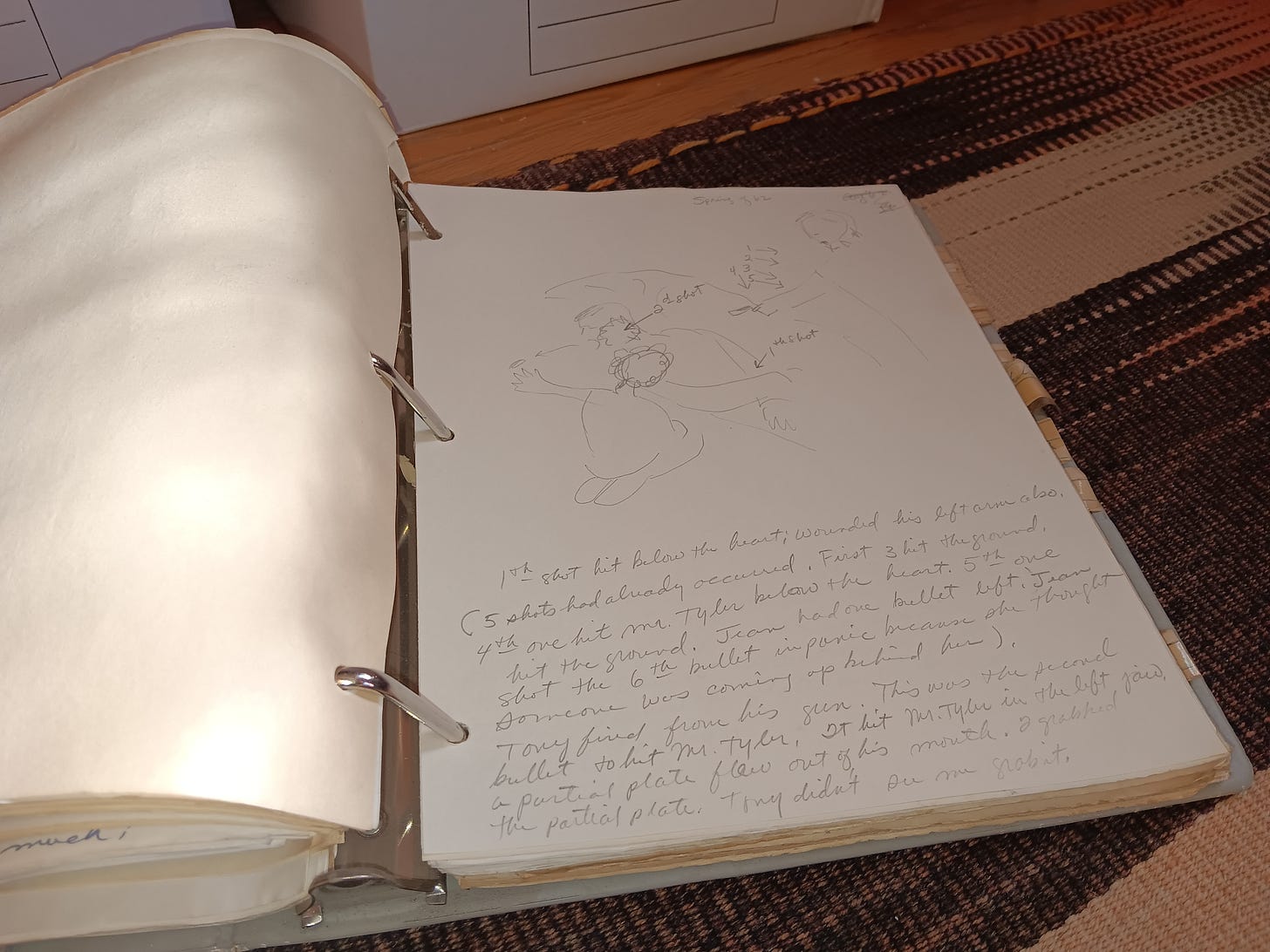

A sketch of the murder of “Mr. Tyler.”

What an incredible story about an incredible story.

Hi, Eva. I'm sorry for your loss. Having said that ... Not that you haven't already given it some thought, but there's a novel in your mother's draft novels/memoirs. You've got a contingent of the characters in this post.

Hope all's well with you and the fam in Phila, and mazel tov to Mathath--Matia--your husband.

Regards,

Rich Pliskin